Global warming from climate change means more evaporation and more moisture in the atmosphere, which means rainfall can be intensified. And intense rainfall and changing landscapes make for more disastrous floods.

Every 1 degree F rise in temperature can mean 4% more water vapor in the air. And since average surface temperature was more than 2 degrees F warmer in 2020 than it was a hundred years ago, there can be nearly 9% more moisture in the air — and clouds.

Recent research shows that in the future, hot, wet conditions (as opposed to hot, dry conditions) are expected to be more common. Heatwaves occurring before heavy rain will dry out the soil, making it less able to absorb water when it rains, increasing the likelihood of flooding.

Used with permission from Climate Central.

What’s more, the way humans have developed natural landscapes, both inland and along rivers and coasts, means more rainwater remains unchecked and unabsorbed at the surface, turning life-giving rains into devastating floods.

Our roads, sidewalks, buildings, shipping canals, dams and agricultural practices have eliminated many natural landscape features that would otherwise slow rainwater’s path across the land and absorb it deeply underground. Stormwater systems are too outdated and undersized to handle the new normal of rain events.

Plus, people continue to place housing in areas where flooding is inevitable. It’s essential to make accurate, up-to-date flood-risk information widely available to help people avoid flood-prone areas — and provide more government planning and funding for community recovery when disaster strikes.

Infographic: How natural infrastructure can reduce flooding (PDF)

Flooding by the numbers

-

$0.0B

Average cost per U.S. flood event, river basin or urban, from excessive rainfall — aside from damage caused by tropical storms, 1980-2021 -

0%

Share of critical infrastructure in the U.S., such as police stations, airports and hospitals, at risk of becoming inoperable due to flooding -

0.0M

Number of U.S. homes and businesses in harm’s way — 67% more than the number on federal flood-risk maps

Flood risk to people is rising

According to research from NASA, the proportion of people across the globe living in flood-prone areas has risen by 20% to 24% since 2000 — 10 times greater than the number previous models had predicted, as climate change drives extreme rainfall, rising sea levels and more intense hurricanes.

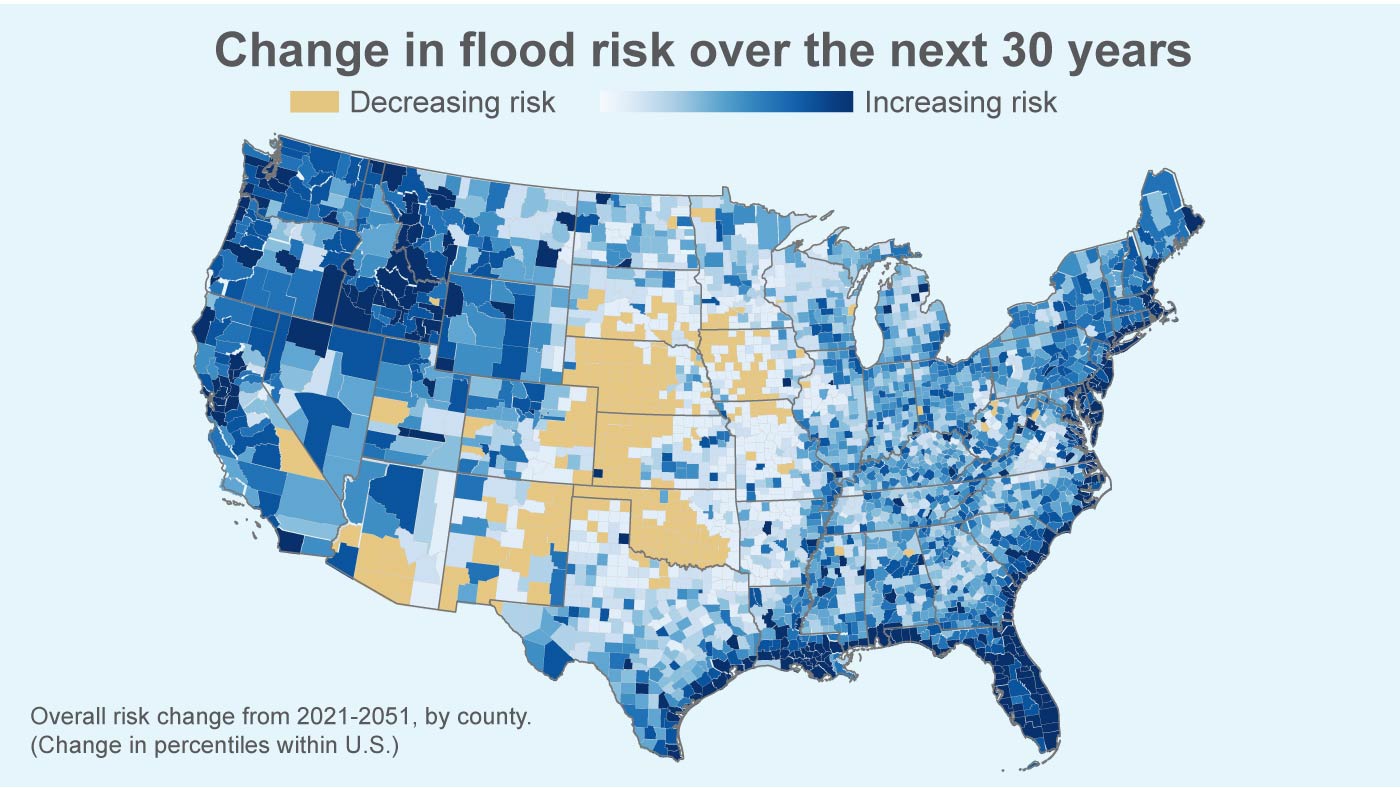

Research from First Street Foundation points to “significant” increasing flood risk over the next 30 years along the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coasts and a “large” jump in risk for the northwestern U.S.

Source: First Street Foundation, 2021 (PDF), page 15, figure 6.

How to minimize growing flood risks

1. Be aware of your flood risk and plan accordingly.

Knowledge is key — especially when it comes to flood risk. That’s why it’s important to look for solutions that give people the power and information needed to make informed decisions for their families.

Solutions include advocating for flood risk disclosure laws, which help inform buyers and renters of their flood risks before moving into a home; identifying gaps and inequities in disaster recovery and insurance; and encouraging relocation from high-risk areas when possible.

2. Incorporate natural infrastructure that absorbs and holds rainwater.

From rural areas to agricultural lands to coastlines to people-packed cities, nature offers a variety of ways to give water somewhere else to go besides homes, businesses, crops and overburdened sewage systems, including:

- Restored wetlands and floodplains, both inland and along coastlines.

- Rebuilt oyster reefs, barrier islands and coastal dunes.

- Restored native trees and plants on the banks of rivers and streams.

- Stormwater-grabbing green roofs on buildings.

- Strips of trees and greenery along streets and sidewalks.

3. Fund and implement holistic community resilience.

Leaders and decision-makers should consider a holistic approach to building lasting community resilience. This means empowering agencies to maintain important services and programs — like trash collection, health care and food assistance — amid challenges from a changing climate.

It also means implementing solutions that provide additional benefits for communities and considering the impact climate change has on populations that are less able to evacuate, recover, relocate or adapt to flooding.

4. Slow global warming and stabilize the climate.

While we address fossil fuels, deforestation and transportation, we must also slash methane pollution, which has more than 80 times the heating power of carbon dioxide for 20 years after its release.

EDF scientists have found that a rapid, full-scale effort to cut methane could slow the speed of the planet’s warming by as much as 30% before midcentury.

Now is the moment to act

Slowing global warming and stabilizing the climate is Job No. 1. The good news: The same tools nature provides to protect us from flooding help us slow global warming and stabilize the climate at the same time.

The solutions are not easy, but we must give floodwaters somewhere to go by incorporating water-absorbing landscapes everywhere — and give people the data they need to make informed choices, along with funding for resilience-building and recovery.

Working with nature instead of against it harnesses a powerful ally as we make our way in this new world — helping us shape that world for the better.

Learn more about extreme weather

MEDIA CONTACT

Samantha Tausendschoen

(715) 220-9930 (office)